WSU Libraries preserve local photo collection susceptible to vinegar syndrome

The grand opening of Dissmore’s. A family’s new washer and dryer. Weddings. Graduations.

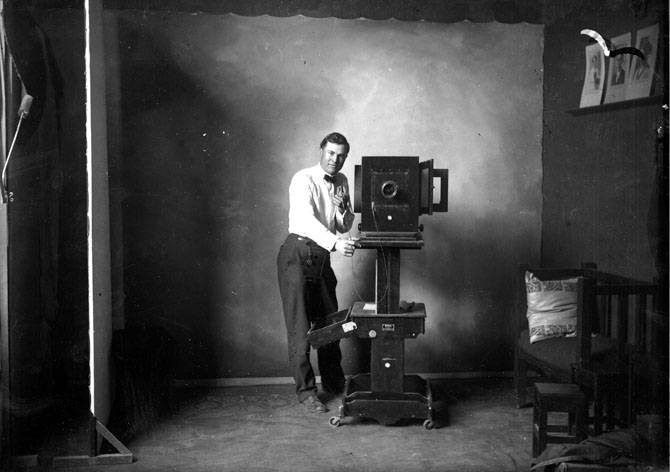

Ralph Raymond Hutchison captured about 50 years of these milestones in black and white, but thousands of his photographs remained hidden. Some became brittle over time.

Until now.

WSU Libraries’ Manuscripts, Archives, and Special Collections initiated a project to digitize the entire Hutchison Studio Photographs collection, expanding access for researchers and community members with ties to the Palouse and WSU.

Negatives from 1923-1970 fill more than 200 boxes in the archives, protected in acid-free folders to slow their deterioration from vinegar syndrome, said Trevor Bond, associate dean for digital initiatives and special collections.

“That process is lending an urgency to this work because if we just let [the negatives] sit on the shelves for too long, the whole collection will go,” he said.

For many of the negatives, their chemicals are breaking down and releasing vinegar. This causes the material to expand, warp, and become brittle.

Thanks to a $5,000 grant from the Sheppard Foundation and other monetary gifts from WSU Libraries’ donors, MASC staff can digitize and preserve the negatives. Digital Projects Manager Joleen Warner and graduate research assistant Kahyun Uhm are prioritizing the collection’s first two boxes, which have more deterioration.

“We are grateful for any funding opportunities that we have to be able to continue preserving history, especially the things that are so obviously in need of attention,” Warner said.

Hutchison grew up on a farm in Endicott, Washington, before moving to Pullman in 1925. There, he founded Hutchison’s Studio, the building where Porchlight Pizza now stands.

Described as “one-bulb Hutchison” for the way he shot a single photograph and was finished immediately after the flash went off, Hutchison and his studio became a cornerstone of community documentation, Bond said. Hutchison also worked for the Washington State College Chinook and Pullman Herald.

In the span of Hutchison’s photography, horse-drawn plows give way to combines, washing machines become electric, and the Ford Model T enters the scene. Bond said they provide valuable insight into advances in technology and are an important record of the region’s history. As Pullman flooded, John F. Kennedy visited the area, and the Pullman High School basketball players won their games, Hutchison documented it all.

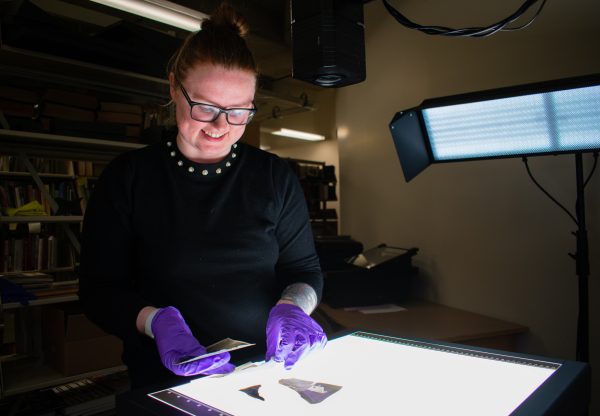

Today, with MASC’s digital camera, light table, and software, Warner and Uhm take high-quality images of Hutchison’s photographs. They capture an “incredible amount of detail,” like the individual tiles on the roof of a house, which is more valuable for researchers looking at the collection online as opposed to studying the small negatives in person, Warner said.

Warner laid the negatives with their glossy side facing downward onto a glowing table and pressed her foot down on the camera’s pedal, triggering a flash. Between sliding the images from their specific envelopes onto the bright surface, Warner must move quickly or the photographs will begin to bend and curl upward, losing their emulsion.

“That’s why a camera with this capability is so important: to preserve every bit of detail of these negatives,” she said. “Give them a few decades, and they won’t exist anymore.”

As MASC staff digitizes the negatives, Bond’s hope is that MASC will share them online through social media pages like Facebook, inviting community members to help identify people and places they recognize.

“I think many community members will be delighted to find family pictures that they either lost or were destroyed over time [and see those] resurface again,” he said.