How Butch came to be: One cat’s journey into WSU fans’ hearts

From riots over stuffed cougars to live animals smuggled on trains, the path to WSU’s beloved mascot was anything but linear.

The Washington Agricultural College’s football team began in 1894. Rather than repeating WAC’s long title again and again, regional newspapers gave the college nicknames like the “farmers” and “the potato diggers”—WAC’s first inklings of a school identity, said University Archivist Mark O’English.

“I’m very much glad that didn’t catch on,” he said. “I don’t see you going past the airport, seeing somebody in a hat, and going, ‘Go diggers!’”

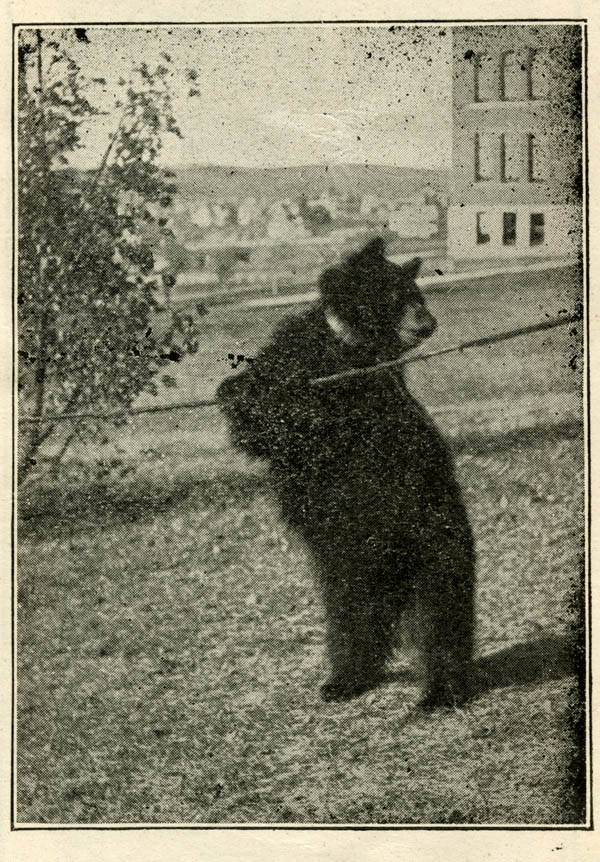

In 1905, WAC’s first good-luck charm took to the field. A little dog named Squirt, who likely belonged to a player on the football team, became a staple on the sidelines until 1908. Toodles the black bear, the football team’s second renowned pet, was present at the same time as Squirt.

Toodles’ legacy began as the football team took a trip by train to Oregon in 1905. They brought along Squirt, who was stolen during the game against Oregon State University, causing players to ransack Corvallis trying to find him. They did not find Squirt, but they did find Toodles.

Players placed a crimson-and-gray sweater on the bear and trotted him up and down the sidelines of the game, refusing to return Toodles despite receiving Squirt at the end of the match. Toodles then joined the football team on the train ride back to WAC.

“I always have a picture in my head of a little old granny with a walker going down the aisle of the train and coming upon a group of college students, who open up to reveal a black bear sitting there in the middle of the train beside them,” O’English said.

As O’English studied local newspapers like the Pullman Herald, he noticed the University of Idaho possessed a black bear mascot a few years before WAC. One article stated, “Bruin, who for over a year has been the mascot of the University of Idaho football team, is no more as on Sunday he was served as steak.”

“Say what you like about the WSU and UI rivalry, [I’m] fairly comfortable saying we are the only one of the two schools who has never eaten our mascot,” O’English said.

On Oct. 15, 1919, a Daily Evergreen article asked for suggestions for a university mascot, but none seemed good enough, O’English said. Ten days later, the football team traveled to California and played the Golden Bears, coming out on top.

Students circulated stories of cartoonists and sports writers commenting on the bears receiving a cougar mauling, which led to a student body meeting on Oct. 28 and the university claiming the cougar as its mascot.

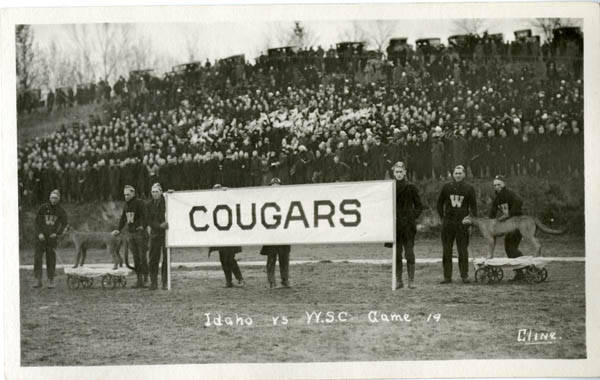

That Friday, Nov. 1, two stuffed cougars were wheeled out on carts for a football game.

“I’m pretty sure you can’t Amazon, two-day mail a cougar in 1919, so I’m guessing these might have been in the Charles R. Conner Museum, and they got these loaned out to them,” O’English said.

Two weeks later, Washington State College played University of Washington, which stole the team’s stuffed cougar after distracting a freshman who was told to guard the cougar with their life. Each year at halftime from 1919-1932, UW cheerleaders rolled the cougar around the field, taunting WSC.

In 1932, the WSC cheerleaders devised a plan to get him back. At halftime, they threw Ken Bement, the smallest team member, into the UW circle. He landed on the cougar, grabbed it, and tried to make a run for it, but UW cheerleaders soon turned on Bement once they realized what was happening.

Although WSC fans had no idea what was going on, they immediately came to Bement’s defense and swarmed the field, causing UW fans to take to the field in response. A riot ensued, delaying the game for over 30 minutes.

“After this riot, everything calms down, and [Bement] relaxes and takes a breath,” O’English said. “In each of his fists, he has one tattered ear of the cougar.”

The cougar ear fragments rested on the wall of Bement’s fraternity until he graduated.

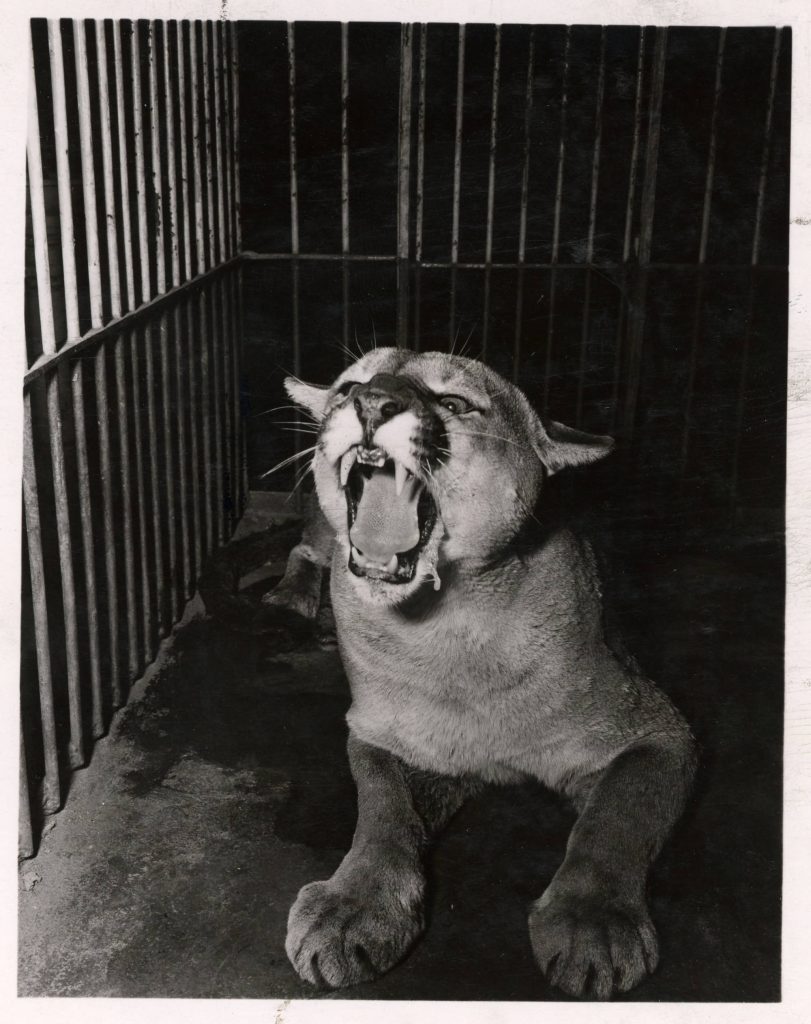

In 1927, WSC received its first, live cougar mascot, which was officially presented to the college by the Washington state governor, a tradition that continued until 1978. WSC named the cougar after the governor at the time, Roland Hartley.

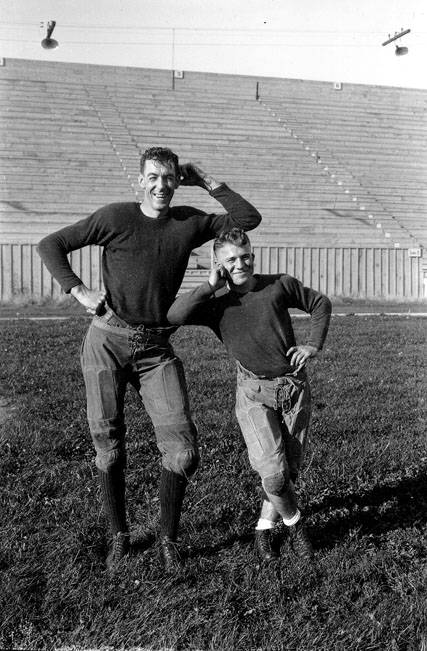

Hartley’s reelection was approaching at the same time as WSC’s game against UW, but he did not want to be associated with the rival of his strongest voter base in Seattle. Instead, he suggested naming the cougar after student Herbert “Butch” Meeker, the five-foot-two quarterback from Spokane.

“I always kind of like that myself, that he’s this tiny little guy who just has to fight three times as hard for everything he’s got,” O’English said.

During World War II, Butch’s legacy extended beyond the confines of the WSC campus. The USS Washington, a ship that served in the South Pacific, held a small bronze statue of Butch, with soldiers rubbing it for luck as they walked by. The ship never took a hit or lost a soldier in enemy combat, and it was also known for sinking the most enemy tonnage.

“There is something touching to me that this ship, which is one of the best regarded and one that kept its soldiers alive more than any other, was being protected by our Butch,” O’English said.

Following its first live cougar, WSC kept six Butches near campus until 1978, when the final Butch died.

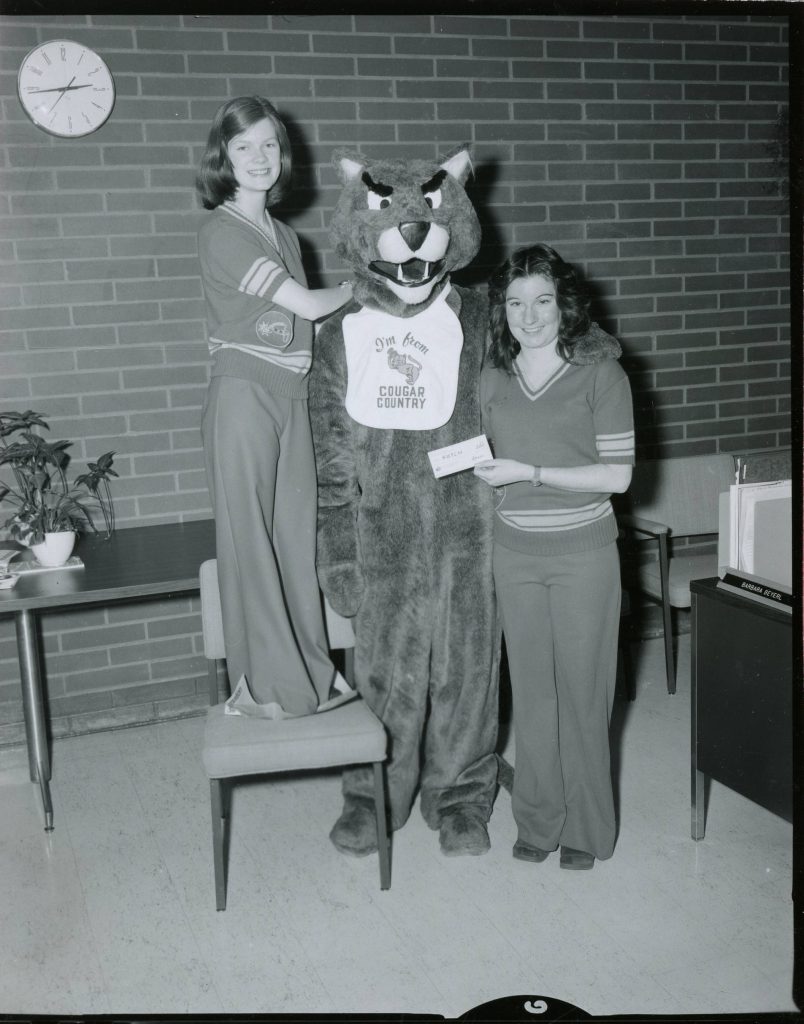

A student poll conducted by the college influenced the shift from a live cougar mascot to a student dressed as a cougar. In 1977 during basketball season, a WSC spirit group decided the college needed an indoor mascot and created a Butch outfit by hand.

Mike Stone, the first face behind the Butch mask, and Cliff Alexander spread papier-mâché on a motorcycle helmet and sewed fabric over it, creating the original rendition of the Butch ensemble.

Butch’s persona evolved into the beloved mascot WSU possesses today, capturing the hearts of students and fans for years to come.