Jane Austen Turns 250: Why the Beloved Author Still Endures Today

By Nella Letizia

To hold a first-edition novel by Jane Austen is a once-in-a-lifetime event for a book lover like me. Sitting in Terrell Library’s Manuscripts, Archives, and Special Collections (MASC) reading room for two days, this authoress first smelled the volumes. A musty essence rose from the pages, composed of imagined, imprinted perfumes and colognes, transferred by the many readers touching the same book again and again over hundreds of years.

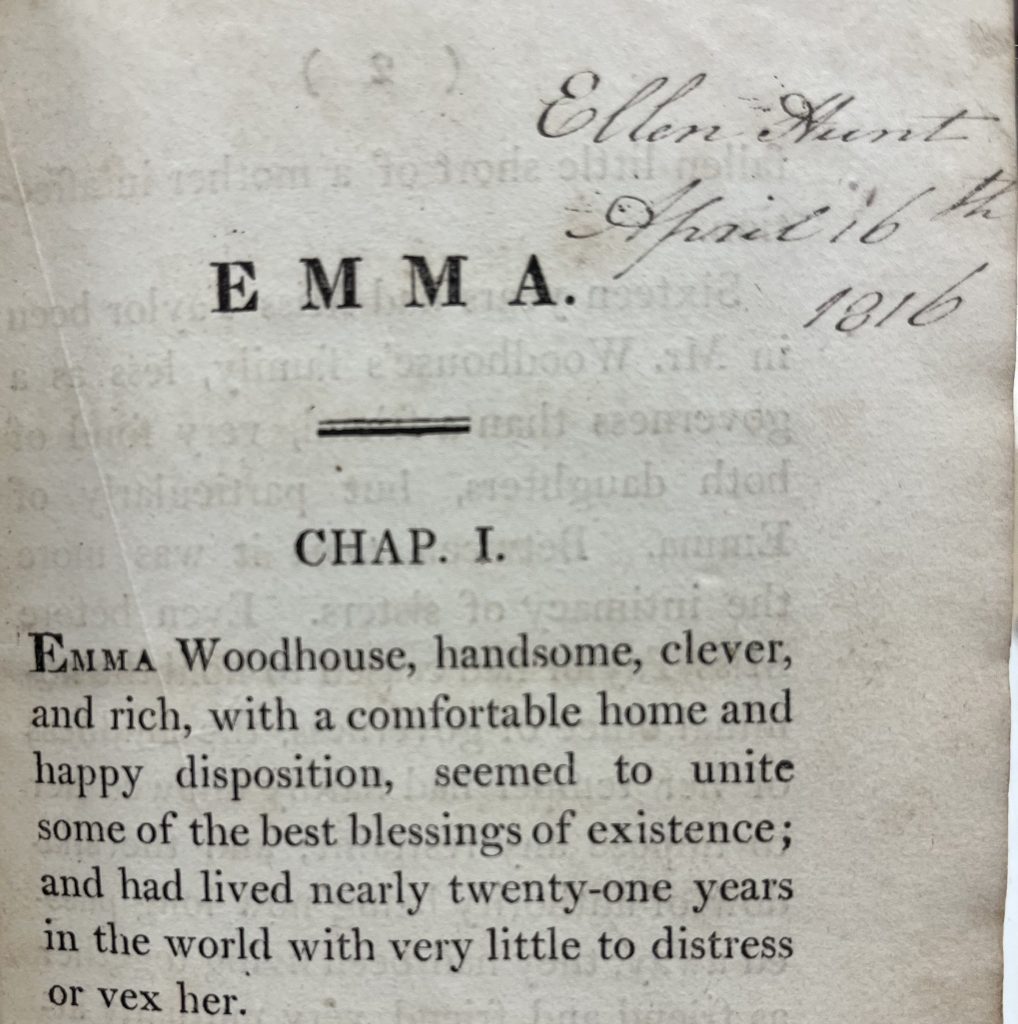

Spidery, beautiful handwriting from unknown hands adorned inside leaves. Ornate bookplates artfully proclaimed ownership. The wear and tear of passing time left buckled, stiff pages and stains. The flaws didn’t matter. It was still pure magic to see them all.

This Tuesday, Dec. 16, is the 250th birthday of the celebrated British author, and WSU Libraries have the great fortune of holding several key treasures in their collections related to Austen, as well as fellow British writer Virginia Woolf, a great admirer. An Austen showcase of these treasures is planned from 10 a.m. to 3 p.m. Tuesday in the MASC reading room.

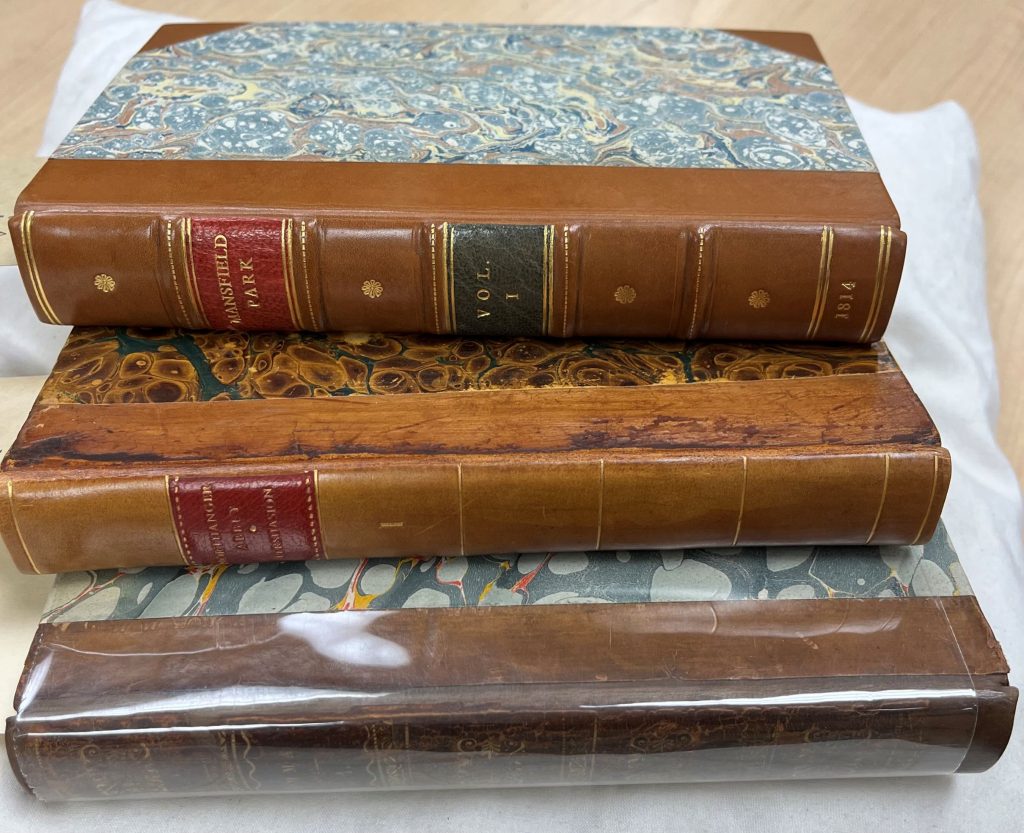

Four first-edition Austen novels reside in WSU’s MASC, given to her alma mater by 1949 alumna Lorraine (Kure) Hanaway: Emma, Mansfield Park, Northanger Abbey, and Persuasion. Three of the editions are largely in their original state, with contemporary bindings, bookplates, and inscriptions.

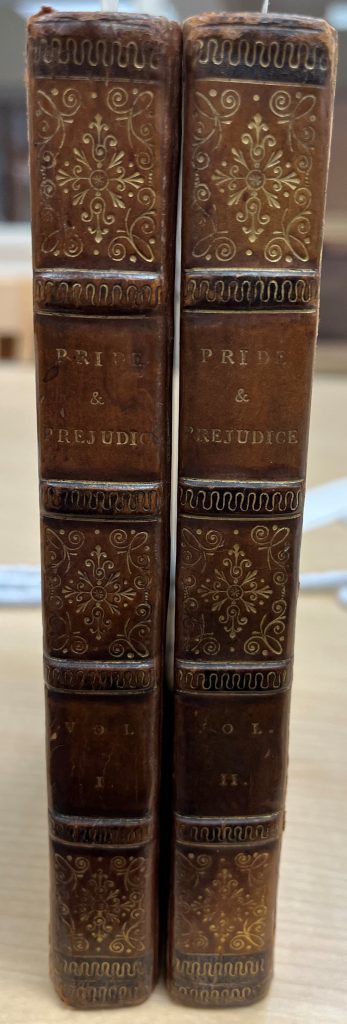

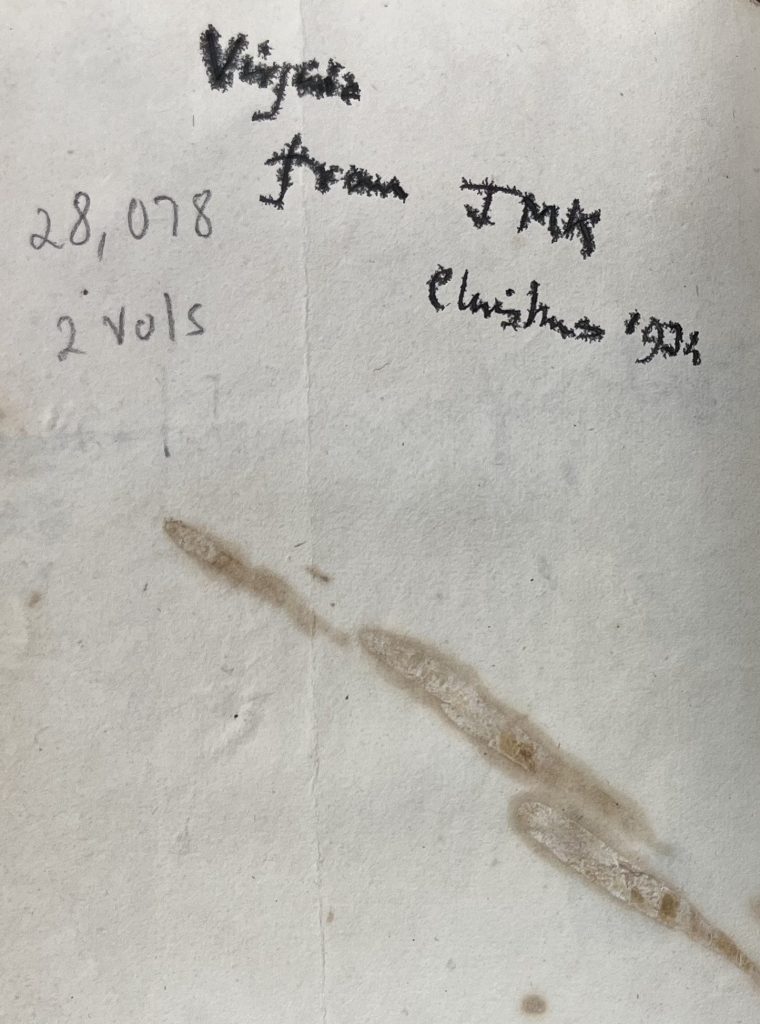

In addition, MASC’s Leonard and Virginia Woolf Library has a two-volume edition of Pride and Prejudice printed in 1817 and given to Virginia by economist John Maynard Keynes, who signed the inside front page. The library also holds The Common Reader, published by the Woolfs’ Hogarth Press in 1925 and graced by an artistic cover created by painter and sister Vanessa Bell. Woolf included an essay on Austen in The Common Reader.

There are also the author’s own words. Lorena O’English, social sciences and government documents librarian, has collected quotations from the few letters that survive from Austen, a prolific correspondent.

From her letters, O’English surmised that Austen appreciated a good dessert (“Good apple pies are a considerable part of our domestic happiness”), sunny weather (“I enjoy it all over me, from top to toe, from right to left, longitudinally, perpendicularly, diagonally; and I cannot but selfishly hope we are to have it last till Christmas—nice, unwholesome, unseasonable, relaxing, close, muggy weather”), and the benefits of aging (“By-the-bye, as I must leave off being young, I find many douceurs [pleasures or gifts in French] in being a sort of chaperon, for I am put on the sofa near the fire, and can drink as much wine as I like”).

“Reading her letters makes her feel very real to me as a person and not just one of my favorite authors,” O’English said. “Her letters are an absolute delight, giving the reader an intimate view into her thoughts, relationships, and life, and you can very easily see the author of Pride and Prejudice in her witty writing.”

‘Her writing feels modern’

In 2021, when WSU Libraries acquired Hanaway’s Austen first editions, Michele Larrow and three other members of the Jane Austen Society of North America, Eastern Washington and Northern Idaho region (JASNA EWANID) came to MASC to see the books in person. Larrow wrote of the experience afterwards; in her article, the four are pictured with a first edition each, donning masks in the second year of the pandemic, but with unmistakable happiness in their eyes.

The regional co-coordinator of JASNA EWANID and a retired psychologist formerly at WSU Counseling and Psychological Services, Larrow said she thinks Austen’s works endure because of her great plots, realistic main characters who are imperfect and relatable, and minor characters who are funny and show the variety of human nature.

Austen explores questions that are central to being human, Larrow said: How should you treat others? What makes a good friend or partner? How do you learn from your mistakes? The author helps readers see the beauty in everyday life and the joy of small gestures of kindness. Her books were written to be reread, with new delights in each reading.

“When we read Austen’s works, we feel an emotional connection with her and her characters, that we share her values and her way of seeing the world,” Larrow said. “Although Austen published during the short period of 1811 to 1817, her writing feels modern.”

Asked what Austen would make of the continued fascination with and love of her novels, Larrow said the author would probably be “amazed and immensely gratified that she is still read.” Austen enjoyed some commercial success when she was alive in terms of book sales, and Pride and Prejudice was popular. Austen was asked to dedicate Emma to the Prince Regent, and Sir Walter Scott reviewed the novel in a prestigious journal in 1816, recognizing the merits of her characters and that she was writing in a new style.

Austen was proud of her writing style that differed from the “romances” with highly improbable plots that were published at the time, Larrow said.

“In a letter to the Prince Regent’s librarian, who had suggested that she write a ‘Historical Romance,’ Austen said, ‘I must keep to my own style and go on in my own Way.’”

Woolf connection

Diane Gillespie, WSU Virginia Woolf scholar and professor emeritus in the Department of English, said Woolf noted in her 1929 A Room of One’s Own how Jane Austen hid her writing from visitors.

Yet despite Austen’s restricted circumstances as a woman, Woolf wrote, “Here was a woman about the year 1800 writing without hate, without bitterness, without fear, without protest, without preaching.” According to Gillespie, she closely observed character and emotion because, as Woolf said, “Her sensibility had been educated for centuries by the influences of the common sitting-room. People’s feelings were impressed on her, personal relations were always before her eyes.”

Woolf also referred to Austen often in her letters and diaries, Gillespie said. In her chapter on Austen in The Common Reader, Woolf wrote:

- “Jane Austen is thus a mistress of much deeper emotion than appears upon the surface. She stimulates us to supply what is not there. What she offers is, apparently, a trifle, yet is composed of something that expands in the reader’s mind and endows with the most enduring form of life scenes which are outwardly trivial. Always the stress is laid upon character.”

- “Her fool is a fool, her snob is a snob, because he departs from the model of sanity and sense which she has in mind, and conveys to us unmistakably even while she makes us laugh. Never did any novelist make more use of an impeccable sense of human values. It is against the disc of an unerring heart, an unfailing good taste, an almost stern morality, that she shows up those deviations from kindness, truth, and sincerity which are among the most delightful things in English literature.”

Gillespie explores more of Woolf’s observations on Austen in her own 1988 book The Sisters’ Arts: The Writing and Painting of Virginia Woolf and Vanessa Bell.

In it, Gillespie writes of how Woolf in 1913 spoke of an Austen novel as if it were a painting able to transport one into an entirely different, self-contained realm: “More than any other novelist she [Austen] fills every inch of her canvas with observation, fashions every sentence into meaning, stuffs up every chink and cranny of the fabric until each novel is a little living world, from which one cannot break off a scene or even a sentence without bleeding it of some of its life.”

‘A sure refuge in silence’

During my visit to MASC, one of the best discoveries was Austen’s December 1817 combined first edition of Northanger Abbey and Persuasion. In it is a “biographical notice” thought to be written by her brother, Henry, five months after Austen’s death. (One JASNA article contributor wrote in 2017 that definitive documentation of Henry’s authorship has never been confirmed.) It is also the first time that the writer of the six anonymously published novels is revealed to be Austen, according to Jane Austen’s House.

The notice with no byline was clearly communicated with the deep affection of one who was close to Austen. The author stated that, “If there be an opinion current in the world, that perfect placidity of temper is not reconcileable [sic] to the most lively imagination, and the keenest relish for wit, such an opinion will be rejected for ever by those who have had the happiness of knowing the authoress of the following works.”

The writer noted that though the “frailties, foibles, and follies” of others could not escape Austen’s attention, she did not portray them in an unkindly way. She instead looked for something that could be excused, forgiven, or forgotten.

“Where extenuation was impossible, she had a sure refuge in silence,” the notice author wrote. “She never uttered either a hasty, a silly, or a severe expression. In short, her temper was as polished as her wit. Nor were her manners inferior to her temper. They were of the happiest kind. No one could be often in her company without feeling a strong desire of obtaining her friendship, and cherishing a hope of having obtained it.”