History of tactile print systems explored in new Vancouver exhibit

Around 1835, Perkins School for the Blind student Henry Stephens noted that he sometimes had to work for days to understand a single page written in Boston Line Type, one of several early tactile print systems for blind and low-vision individuals. Deafblind author Helen Keller wrote during the 1860s that another system, New York Point, wore her out trying to decipher such sprawling letters.

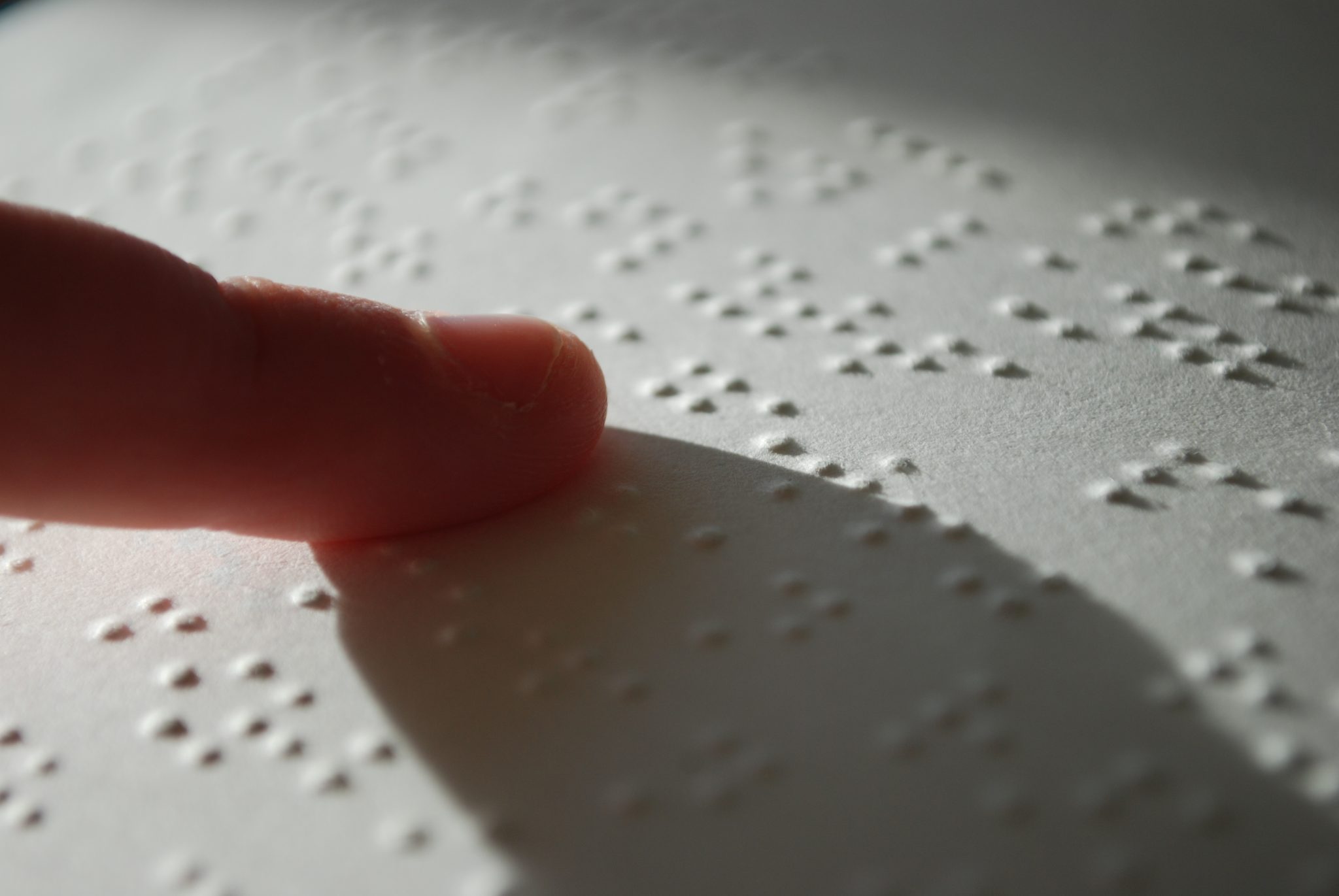

A Washington State University-curated exhibit at the Washington State School for the Blind in Vancouver explores the 100-year history of tactile print systems developed in the 19th and early 20th centuries, how blind people read and wrote with them, and how braille emerged as the leading system. Called “War of the Dots: A Short History of Tactile Print,” the exhibit runs through June. Visitors to the WSSB should schedule ahead for a time to stop by.

WSU Pullman Scholarly Communication Librarian Talea Anderson, WSU Vancouver Library Archivist Robert Schimelpfenig, and WSSB Superintendent Scott McCallum collaborated on the exhibit. “We wanted to highlight the work that blind people did to advocate for braille,” Anderson said. “The title ‘War of the Dots’ comes from a book written by Robert Irwin, a blind graduate of Washington State School for the Blind. He outlined the many steps blind people took to put into place a better and more effective reading/writing system.”

Unequal access to information

Before tactile print systems, blind people had little access to print, according to exhibit curators. Then in 1786, Valentin Haüy tried pressing letters into damp paper, marking the first significant advance in tactile print and opening the door for other systems: braille in 1829, Boston Line Type in 1835, Moon Type in 1845, and New York Point in the 1860s.

But English speakers couldn’t agree on a common system of tactile print. Educators—mostly sighted men—argued over which system was better. Caught in the debate, blind people had to learn as many as five or six different systems to read information. “The options appear overwhelming and confusing,” Schimelpfenig said. “A blind person who had gained literacy through one system often discovered that the books they wanted to access were exclusively printed in another format, requiring familiarity with a totally different system of code.”

The winner is…

Today, almost 200 years after Louis Braille proposed his system, braille is used by speakers of more than 130 languages around the world. How did it win the war of the dots? Blind students used and shared it, sometimes in secret, exhibit curators say. Blind educators and activists raised funds to study braille’s effectiveness, established research committees, collected data, and advocated for support. By 1932, all English-speaking countries used the same system of tactile print.

“Blind communities worked for braille,” Anderson said. “It wasn’t just ‘given’ to them.” “I see braille as a force for democratization,” Schimelpfenig said. “Robert Irwin was a voice delineating systems created by those who think they know what is best for the blind from those who want the blind to determine what is best for themselves. This is something that needs to be recognized and talked about more.”

Exhibit part of Mellon Fellowship

Sponsored by the Rare Book School, “War of the Dots” is part of Anderson’s work as an Andrew W. Mellon Fellow for Diversity, Inclusion, and Cultural Heritage. In addition to presenting projects and symposia, participants took part in a field school, visiting museums and archives working to spotlight underserved collections and integrate accessibility. “All throughout, I’ve been really inspired by the ideas, passions, and interests of others who took part in this fellowship,” Anderson said. “I’ve also appreciated having the space and time to cultivate a relationship with Washington State School for the Blind. I’m grateful that the fellowship helped make that possible.”