WSU Press Book Tells Stories Behind Washington Round Barns

Only a tiny percentage of the approximately 3,000 barns in Washington are round. Enchanted by their beauty, complexity, and historical significance, Tom and Helen Bartuska have been researching, visiting, and photographing the Pacific Northwest’s round barns since the 1960s, shortly after Tom accepted a teaching position at Washington State University’s architecture department.

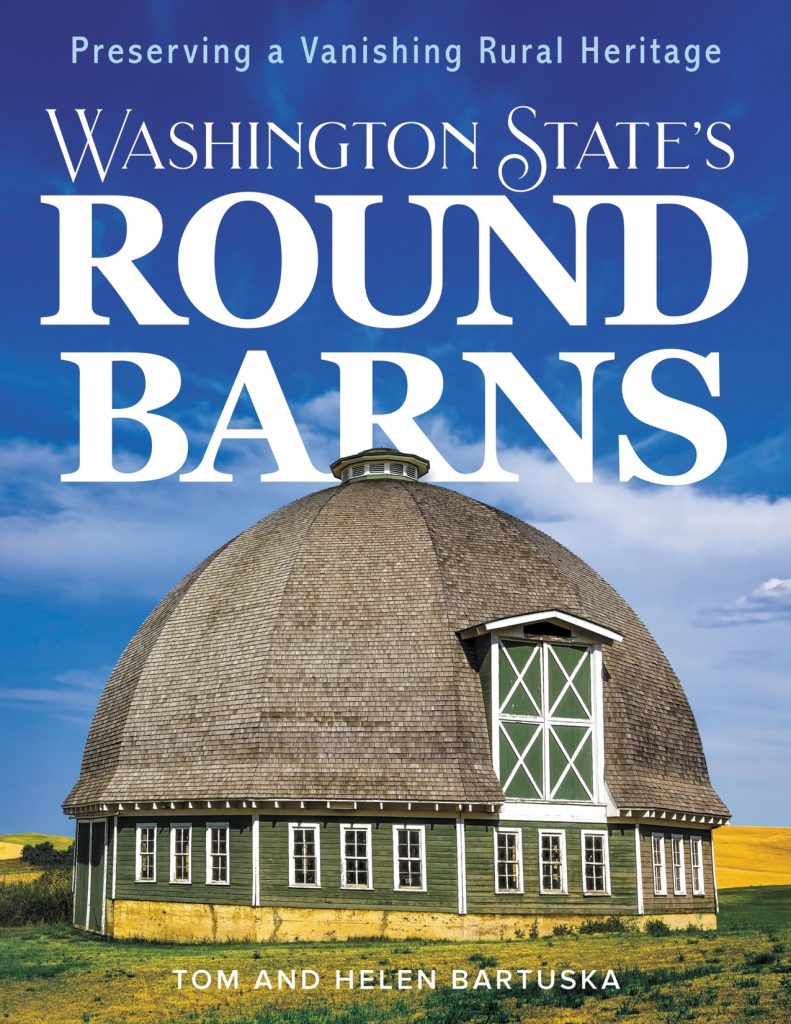

“Barns—especially round barns—are unfortunately vanishing from the rural landscape, yet they have an important and fascinating tale to convey,” the Bartuskas say. “They are beautiful icons of our country’s landscape and are an important part of our history and cultural heritage.”

Focusing on agricultural structures over 50 years old with at least two stories, the pair eventually compiled a list of 21 buildings and made it their mission to create a comprehensive inventory—recording who built each one and when, original and current uses, individual characteristics, construction details, and anecdotes they learned along the way. Their work is described in a new WSU Press book, Washington State’s Round Barns: Preserving a Vanishing Rural Heritage.

Since most of the barns were constructed in the early 1900s, the couple explored archives to gather historic photographs and paperwork. When possible, they also took interior and exterior photographs and talked with owners about each structure’s story, revisiting several sites to document how the barns changed over time.

For example, Washington’s oldest known round barn was originally located on a hill overlooking Cathlamet and the Columbia River, but now sits in a field behind the town’s cemetery. It was built around a large, live tree. After completion, the tree was removed, but the cutoff trunk remains as an integral part of the roof.

In addition, the Bartuskas researched round barns’ fascinating history and development across the United States—including similarities and differences, various construction methods and designs, advantages and disadvantages, and the reasons they were built.

Perhaps surprisingly, one reason is that they were cheaper. Utilizing shared labor from extended family and neighbors made the cost of materials the largest expense. One early 1900s report calculated total materials savings for a 60-foot-diameter round barn versus an equivalent-sized, plank-framed rectangular barn as $378.77, or 36 percent.

Sadly, the structures continue to succumb to economic and technological changes, as well as to fire, disrepair, and the forces of nature. Seven of the documented Washington barns no longer exist, and several of the remaining 14 are in peril. Hoping to inspire others to help maintain, preserve, and restore these unique cultural icons, the authors added examples of successful reuse and creative conservation nationwide, along with ongoing efforts to save other types of barns, buildings, and rural communities.

A nonprofit academic publisher associated with WSU in Pullman, WSU Press concentrates on telling unique, focused stories of the Northwest. The press, now located at the WSU Libraries, has published over 200 titles and received numerous honors and awards.